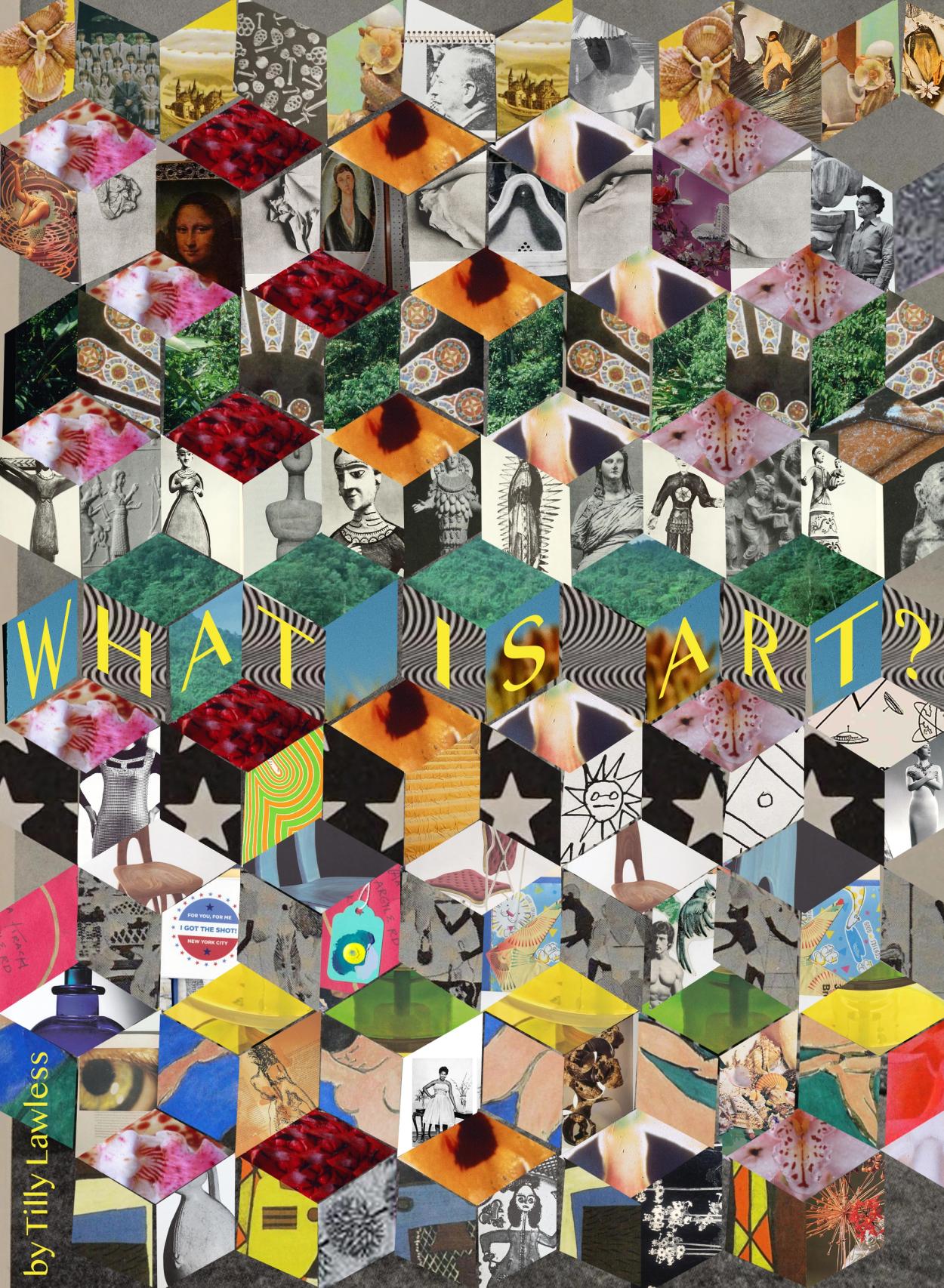

What Is Art?

Across centuries and continents, Tilly Lawless enters into a dialogue with Leo Tolstoy to revisit the timeless questions posed in his iconic essay ‘What is Art?’ Who gets to make art? Who gets to decide whether art is good? And how do artists make a living in an era where their craft is misunderstood, minimized, and downright ignored?

Tolstoy’s 1897 essay ‘What is Art?’ is a few hundred pages and is both a sharp critique of European thinkers of the preceding centuries and a winding meditation on who and what art serves in a society divided by class. I couldn’t possibly comment on all of it, but I was surprised by how much struck me and remained pertinent to now; his declaration that attempting to define ‘beauty’ or ‘taste’ is both impossible and a distraction from art, that art is intrinsic to the human experience and that taste will always be dependent on the beholder, and that the rich have become the public arbiters of art (being both more able to consume it and controlling the platforms through which it is commented on), all rang true to me.

They also confirmed my discomfort with the ‘grading’ of art, through stars and awards, which to me does it a disservice as art can’t be approached as an exact science and it inevitably reflects the subjectivity of the viewer. Of course, criticism can be illuminatory when it recognises this subjectivity, as can, say, an analysis on your own reaction to a work or how the way in which it was crafted ties to the context in which it was created, but I don’t believe in the critic as an objective marker. (Related to this, I think Tolstoy would agree with the Australian artist Evelyn Araluen, who in her acceptance speech at this year’s Stella Awards, declared that artists shouldn’t be struggling and competing against each other to win an award to sustain them financially, but instead given a basic living wage.)

He argues that art is ultimately about communication, the deliberate transference of emotion from one person to another. I concur, though I think he leaves out another transference that is just as valuable; the transmitting of thought—not concrete unassailable thought, as propaganda seeks to, but the process of thinking itself. Using his own essay as an example, he speaks of it being a vain redundancy to attempt to define relative things as absolute, whereas I think there is a beauty in the journey itself, in the questioning and the raising of thoughts that send off a ripple effect of thoughts in the reader; his piece is wonderful to read even in the parts that can’t reach the ‘truth’ of the matter. There are many works of art that I find confronting or unappealing visually, and certainly do not transmit a particular emotion, but force me to reckon with assumptions or interrogate certain things, for example Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’.

Tolstoy points out that art requires intent behind it, otherwise there is nothing to differentiate the beauty of art from the beauty of nature, and he makes use of the example of a blue sky. In a fascinating coincidence, that is the same example that Olive Schreiner uses in Lynsey’s monologue in ‘The Story of an African Farm’ to argue that beauty does not need to be intricate or complicated, that it is the monotony of a cloudless blue sky that makes it beautiful. Tied to this is his criticism of art that is intentionally over-complicated, obfuscating with layers of complexity that force the viewer to jump through hoops to prove their understanding and only let in certain people (academia often does this, a notorious example being Foucault).

For Tolstoy, art is only great art if it is accessible and comprehensible to great numbers of people. I largely agree with him; in my own work I always aim to make difficult matters simple, rather than the other way around; ‘to be overtly political but also totally accessible, and produce something beautiful’ as Atong Atem says. However, I think there is also a kind of art that seeks to be esoteric or niche by requiring you to actively play with it to decipher it, and that gives you a satisfaction in cracking it, makes you feel clever in interpreting all the references correctly. I think there are kinds of poetry that do this, and also memes that rely on intertextuality, and a grasp of the language of the internet. Interestingly, I think Tolstoy would’ve been in full support of the other kind of memes, which are those that attempt to communicate a specific emotion or experience in a simplified way so as to be universal.

He also believed that superior art combines aesthetics with morality, with that morality coming from religion (and Christianity as the highest form). I disagree with his premise, as I think secular people have the ability to create and be moved by art just as much as religious people for there is an existing morality that pre-dates religion, and religion is simply the manifestation and depiction of that morality. Religion, to me, is an attempt to transcribe what we know deep inside us, an innate morality, and I don’t think secular people have ‘lost all faith’ as he claims or ‘having no religion believe in nothing at all’; I think one can have faith in other things, such as a goodness of humanity.

Further from that, when he argues that art should serve a purpose beyond the individual, to a larger social purpose and not just be ‘art for art’s sake’, I find I mostly agree with him. I don’t believe that art has to serve a greater social purpose in order to be art, but I find that the art I am most moved by personally does. For me, Oscar Wilde’s best work is by far ‘De Profundis’, which he wrote from jail. And the reason I find it so is because, for the first time, he really begins to grapple with social issues beyond himself and recognise that in his life up till then he has been completely cushioned from them. ‘De Profundis’ reaches a depth (hinted at in the title, Latin for ‘from the depths’) that he hadn’t reached previously and combines his incredible writing form with topics that lead you to not only feel his emotion, but to think further upon what he says. Molly Crapabble’s autobiography ‘Drawing Blood’ is a modern example of a work that similarly goes into the development of an artist who created with only aesthetic in mind to being one who realises the radical power and potential in art.

Of course, any work produced entirely with the aim of imparting morals runs the risk of becoming toothless and dull; the Victorian era generated thousands of novels with a calculated moralistic tone and there are few that endure. ‘Guy of Redclyffe’, ‘Little Women’ and ‘Princess and the Goblin’ being three that do, most of the rest are so imbued with value lessons that they have crossed into the saccharine. They lack the punch of David Wojnarowicz jacket for example, ‘If I die of AIDS forget – forget burial – just drop my body on the steps of the F.D.A.’, a work of art Tolstoy would’ve approved of for the communal change it could bring, focused on the bettering of a collective rather than the pleasing of an individual viewer.

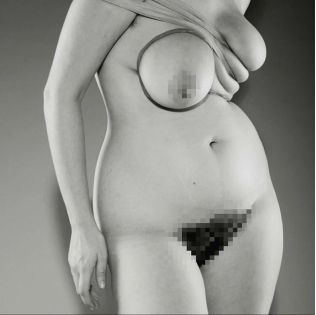

I think emotion is an embodied experience, and that along with eliciting laughter or tears art can elicit another involuntary response – hardness or wetness. Unlike Tolstoy, I think that sexual desire is a valid response to art, not a symptom of decadence, art corrupted by the elite as he states. It is important to note that in the period that he wrote erotica was rare and collected by the rich, rather than this era of proliferation of porn in which it is so readily available that it has gone from being seen as a vice of the genteel to trashy. I am of the opinion that art and porn can coexist, and that just because something turns you on does not brand it as ‘low art’. I think author Alan Moore argues this more successfully and evidentially than I can in his graphic novel ‘Lost Girls’ with illustrator Melinda Gebbie.

Sexual desire is one of the biggest drivers we have in life, a hunger that moves so much of our social interactions and a feeling strong enough for some of us to even pit our futures upon. I think it is absurd to suggest that once it is initiated the aesthetic or political value of a work of art is undone, and it somehow moves into another category entirely. Tolstoy can concede that turning the corpses of animals into something delicious can be a form of art, except writing of stranger’s bodies in a way that doesn’t give the ick but instead creates a wanting is somehow not. I also think porn is often a kind of melodrama (containing the heightened emotion, stock characters and sensationalism of the genre), a genre which has fallen out of favour in the western world since its silent movie era heyday. In some places melodrama can still coincide with accepted and recognised art, think the Japanese film ‘Battle Royale’, however we retain the vestiges of it only in things we class as ‘b grade’ such as horror, so porn is condemned by its unpopular form as well as content.

Tolstoy also states that whilst the rich only have three feelings in their art – pride, sexual desire and weariness of life – they are assumed to be more complicated and interesting than working class people. Whilst I can see how he reached that conclusion, as art was dominated and continues to be dominated by the rich for various reasons (they have more leisure time to create, have more social connections to succeed etc) and so inevitably we do hear more of upper middle class and upper class preoccupations in art, I think that those feelings he describes are more universal feelings of the human condition. If you turn to country music for example, which is often a true mourning and expression of the disenfranchisement of (largely white) working class people you will find all of those themes, and the latter one especially is an existential angst that is perhaps even exacerbated with modern life.