A Sexologist's Dinner Party

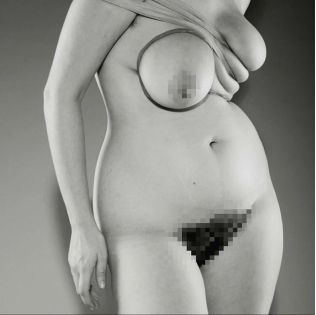

Cheryl Fagan gets real with her nearest and dearest about overcoming sexual shame, over wine and pasta at her Sydney home.

Growing up, I was that kid who was always asking questions about sex, sometimes loudly and in public. I’m thankful now that I was apparently resistant to the shame that so many of us end up internalising at such a young age. My preoccupation with the subject became much more, and after high school I spent a decade leading discussion groups with young adults and studying, getting a bachelors in psychology and a masters in sexual and reproductive heath. I’m also a member of the Society of Australian Sexologists and certified by the American Association of Sex Educators, Counsellors and Therapists.

In 2018 I released On Top: Your Personal Study Guide to Holistic Sexuality, an educational resource for teenagers and community groups, and began hosting On Top Dinner Parties, assembling friends and people from my community around the dinner table for good food, good drinks and conversations about my favourite topic. You can see photo evidence of one such gathering on these pages. For me, it’s more than a career—it’s a calling. One of my main goals is to break down the barriers that prevent us from talking openly and honestly about sex with our friends, and so for Par Femme’s first issue, I got deep with two of mine about how our experiences growing up can inform the way we talk about sex in adulthood.

Aleeya Hachem is a fertility counsellor and fellow sexologist, and Chelsea Leyland is a DJ, producer and co-founder of Looni, a new company hoping to illuminate the menstrual cycle.

Cheryl: I want to know—how was sex talked about in your family when you were younger? And what was sex ed like at school for you?

Chelsea: We had a few sex ed classes, but the only memory that I have was putting a condom on a banana and that’s about as far as it went. I don’t remember being taught about how to talk about sex, about what sex or pleasure is, or anything in terms of the menstrual cycle. In my family, it was probably a bit too open for my liking! Now that I’m on the other side of 30 I’m grateful for it, but it’s taken a level of maturity to appreciate that openness. My parents were always very vocal about their healthy sex life and have always spoken about sex with humour. They put great importance on sex in relationships, so I’ve always had that awareness. As cringeworthy as it was, it allowed me the space to be open and become the person I am now—someone who feels comfortable talking about sex and pleasure.

Aleeya: So interesting that your family was so open, and the juxtaposition between that and your sex ed.

Chelsea: Yeah. School, right?

Cheryl: I feel like I had a similar experience in that my parents were quite open, but then sex ed in seventh grade California was just, like, fear tactics. Like: Use condoms or you will get an STD. Then my parents started taking us to church and I started learning more shameful messages around sex. It was quite confusing as an adolescent trying to figure out my values. But I’m still so thankful that my parents were open about it— I know that’s not a lot of people’s experience.

Aleeya: Yeah, definitely. Sex was never really spoken about in my family, coming from quite a strict Muslim upbringing. I remember my mum saying you only have sex when you get married, but I was quite curious about it growing up. I went to an all girls school, so sex ed was very much focused on pregnancy, preventing pregnancy and the menstrual cycle. We passed around different methods of contraception in grade six, so we were all, like, 12—we had no idea what was going on. Pleasure wasn’t spoken about, or communication. Consent wasn’t even really spoken about, which I find really interesting. Cheryl, when we went to uni together and did that mandatory consent subject, that was the first time that I’ve ever really learned about consent! And I was 28! Crazy.

Chelsea: Yes! I think that a lot of people feel that way. I think that’s partly why that British show I Will Destroy You did so well, because of the focus on consent. I don’t think you’re alone—it’s not really been a mainstream conversation until recently, which is crazy.

Cheryl: I think it’s a big part of what the school system misses out on. We should learn how to communicate about sex and what healthy relationships look like, and that includes navigating consent and being able to speak up for yourself. To communicate what you find pleasurable—what you like, what you dislike... That is not really a part of sex education and it really should be. It’s so much a part of the sexual experience. Looking back now, Chelsea, you can see how your parents openly talking about it has helped you to be able to communicate about sex and pleasure—can you think of other ways that those formative years impacted the sexual person you are today?

Chelsea: When we talk about consent we’re talking about communication. As young women I think we weren’t empowered to talk about our sexual needs. It was through porn, or through the media; you picked up Cosmopolitan and it was always about ‘pleasing the man’. It’s a symptom of living under the patriarchy to some extent. One thing we don’t teach people is that you can say, ‘I want to see the person that I’m having sex with feeling pleasure’.

In a partnership, each person wants to see and feel the other person experiencing that pleasure, and that creates pleasure for you as well. I feel very lucky as a woman to be living in this time, and as a woman with the background that I have. I think as women we’re always taught to be a little more demure and not ask for what we want, ’cause we don’t wanna come across as being aggressive. It’s like if a man asks for what he wants it’s normal, but if a woman asks for what she wants God forbid she comes across as aggressive. I think there’s so many layers to it.

Cheryl: It’s so complex, there’s a lot of unlearning involved. Aleeya, you have a career in sexual health and fertility, so I guess those years definitely had an impact on you, personally and professionally.

Aleeya: Absolutely. I think so much of my work now is working with young women in unlearning those things and educating them around pleasure and asking for what you want. We are taught that we observe, that we come second to men’s pleasure. This definitely shaped who I am: not having that education and insight into what sex could be actually ended up leading to a career. I’m really grateful that I get to help make other people’s experiences more fulfilling and more pleasurable than my own growing up.

Chelsea: I love that. It’s so interesting how sometimes light comes out of a negative experience. In a way it can be a gift when we don’t have what we need, because we can turn it around and it teaches us so much more on such a deeper level.

Cheryl: Yeah, I can still relate to that. I had so many questions as a young person, and I remember actually starting to find answers, but feeling like none of my friends knew about any of it, especially my girlfriends! They’re all having sex and they don’t enjoy it—they’ve never had orgasms, they’re faking orgasms, all these different things... I was like, why haven’t we learned all this other stuff? It’s so much more holistic. There’s so much to it and it can be so amazing, like a spiritual and emotional experience. But in sex ed it’s just about biology, or it’s fear based—use a condom or else you’ll get pregnant and get an STD.

What were your experiences like with menstrual health and fertility? My mum was so open, I would see her change her tampons. She was like, This is a tampon, learn how to use it. You’re not coming out of the bathroom until you figure it out. I have friends who never spoke to their mothers when they got their period. Their mums just started leaving pads underneath the bathroom cabinet.

Chelsea: Like you, my earliest memories are my mother walking around naked, so I remember from a very young age seeing this blue string between her legs and always thinking it was a bit weird—I didn’t really enjoy seeing it—but it was just very normal. I think my mum explained to me at a very young age what a period was, and I remember feeling like I had been led in on this little secret that not a lot of my friends knew about. I remember telling a few friends at primary school and one of them asking my mum about it, ’cause she obviously felt that she couldn’t ask hers. I think a lot of this as well comes back to nudity. It’s so important to start with that openness, and to do it before we even start talking about periods or sex—that it’s not shameful to show your body. I went to boarding school from age 11, and there wasn’t a conversation around pain.

I was lucky because I was living with a whole bunch of women, so we learned to be really open, and our periods would sync up—even though I know now that’s not scientifically proven [laughs]. But as someone that has suffered from pretty horrific endometriosis, I don’t feeling like I knew a whole bunch of other women that were also experiencing pain like that. One in nine women suffer endometriosis—it’s incredibly common. I know a ton of women now, but when I started getting pain like that at 17, I don’t remember knowing anyone else that was suffering like that.

And maybe that was because I wasn’t as open about it beyond going to the doctor. It also comes back to how we need to stop normalising pain for women. I was told for years that my pain was normal, that it was part and parcel of being a woman. It took seven years to have a laparoscopic procedure and finally be diagnosed with endometriosis. I look back at that whole period of my life with not a very positive feeling. I think there’s so much work that we need to do to open up this conversation. Periods shouldn’t be taboo. You have to be your own best advocate, but it shouldn’t be that way.

‘Pleasure is just really, really, really important! It teaches us about our body—it teaches us about what we like and how we want to be touched.’

Cheryl: Yeah. Like you said, it’s a common experience, but because you are told that it’s part of being a woman, you just think it’s normal. Some of my friends go through so much pain and have never gone to get help, or they were just put on the pill from a really young age when actually something more serious could be going on. There’s so much work that needs to be done.

Chelsea: That is a memory I have from school—the school’s position was to push the contraceptive pill. It almost became this trendy thing that you were encouraged to do ’cause everyone was doing it. And this was before anyone was even having sex! It was like, Oh, you’ve got period pain? Take synthetic hormones. Oh you’re breaking out? You’ve got three pimples on your face? Take synthetic hormones. That was very much what was recommended in high school, and it always kind of made me feel like I wasn’t making intelligent choices because I wasn’t taking synthetic hormones.

Cheryl: All this ties in to what you’re doing with Looni, which is really exciting. Can you give us the spiel?

Chelsea: So, Looni is a women’s health company that we are getting ready to launch, and our focus is on the menstrual cycle, offering clinically formulated, innovative products as well as education. It really touches on so many points that we are talking about now. We’re really trying to continue to open up this conversation and help educate women and young girls on some of the topics that my co-founder and I felt that, growing up, were just not addressed. And that’s coming from someone like myself who came from a family where everything felt very open compared to most people. I went to a relatively progressive co-ed school, and still, you know, there were just so many things that made the idea of wanting to discover your body as a woman feel like something was wrong with you. It really stays with you. It scars you. Even with small things, like, I don’t know, vaginal discharge making you feel like a freak, like there’s something wrong with you, you feel so much shame—that’s what we want to try and shift and change, and it starts at such an early age.

Aleeya: I’m so excited that my daughter gets to grow up in a world where this stuff is so openly spoken about and that there are all these amazing products and innovations available and conversations being had. I don’t know whether it’s because I work in the field and I’m so aware of what’s going on right now, but I feel like back when we were younger, like, cervical fluid was not spoken about [laughs]. There’s still a lot of learning to do, though. For example a lot of women in their twenties think that they can get pregnant at any time in their cycle, when there are actually only 24 hours where you can get pregnant. They fear having sex because of pregnancy, and the fear just sticks. I’m just so relieved that we’re shifting in a different direction.

Cheryl: Do you talk about sexual wellness with friends?

Chelsea: Yeah, I think it’s really important. Masturbation is one topic that’s not widely spoken about amongst women, and it’s a fantastic tool for relaxation to help decrease cortisol from the body. Also, pleasure is just really, really, really important! It teaches us about our body—it teaches us about what we like and how we want to be touched. When there’s a lot of shame around that for whatever reason, or if it’s just something that you haven’t really explored, if you are talking about that with other women in your community then you might feel free to try something new that could be really beneficial for your health overall. You know, I spent five years in relationship in my early twenties and we stopped having sex due to issues that my partner was experiencing.

I felt a lot of shame around that, and it wasn’t something I felt like I could go and speak to my mother about. It took me a really long time to open up, even in therapy. I remember bringing it up with a couple of friends once during the relationship, and they reacted in a way that made me realise it wasn’t normal. Even getting that response from them was helpful. Once I got out of the relationship I was able to talk about it much more freely. It’s just so important to be open and have these conversations, because it helps educate us. It helps give us the support we need, and that sense of community.

Aleeya: Yeah, definitely. I’m not sure if ‘sisterhood’ is the right word, but to have people around you who are sort of going through similar experiences, people who you can lean on, I think it does work to normalise and destigmatise these things. It also works to provide you with that assurance that you’re okay. You know, sexologists weren’t really a thing until recently, as in we didn’t really know that that was an avenue. You could go speak to a therapist, but they’re not necessarily trained in sexual stuff. GPs aren’t necessarily trained in how to deal with sexual problems and they often just send you to a gyno or put you on oral contraception. Like, that’s all they do sometimes.

Chelsea: It’s just so hard for people to talk about sex. The more we help break it down and normalise it, I think we can all feel a lot more comfortable and empowered.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.